New standards for A&E – Trusts may struggle to meet them – Feb 2021

It is now likely that the four hour standard for A&E will be replaced by a bundle of new measures. Now we know what the metrics are likely to be, we make practical suggestions on how to drive up performance.

In December 2020 NHS England published ‘Transformation of urgent and emergency care: models of care and measurement‘ [1]. The consultation period for consideration of this proposal for a bundle of measures ended on Friday 12 February 2021.

The Royal College of Emergency Medicine has now published its formal response to the Clinical Review of Standards (CRS) consultation [2] and are broadly in favour of swapping a bundle of measures for the single four hour standard introduced in NHS in England in 2004. That standard required 95% of patients to be seen, admitted, transferred, or discharged within four hours of arrival in Emergency Departments. Apledge to meet the standard was introduced into the NHS constitution in 2009. However since 2015 that pledge has not been met nationally. Although the standard initially reduced waiting times in ED, and RCEM defended the target in 2018 [3], there have also been criticisms relating to how this measure allows some ‘gaming’ [4] and distorts practices (with hurried admissions or transfers to ‘Clinical Decision Units’ before the deadline). One point, often ignored, is that this measure discounts differences in case-mix attending different trusts [5].

The relationship between ‘Exit block’, very high hospital bed occupancy rates (even before the Covid 19 pandemic) and failure to meet the four hour standard is evident and obvious. The hope is now that the new bundle of measures will allow some ‘dissection’ between system-wide and ED-specific issues. However, this is also an opportunity for a rethink about the whole system.

SHARING SOME INSIGHTS

We believe that few ED & NHS trust managers have access to a sufficiently detailed picture of the complex interplay of components of their local A&E systems. In all likelihood many individual improvements will be needed to tune performance. This is our guideline of where to place the metaphorical spanners to achieve some early ‘wins’.

We can also share insights into the workings of a London based trust where we have monitored detailed timings for key events in the patients journeys for two cohorts of patients: ED arrivals and attendees at the co-located Urgent Treatment Centre (UTC).

Time to initial assessment (% < 15 minutes)

We believe it is necessary to replace triage and streaming with an assisted initial assessment which includes preliminary investigation selection and treatment evaluation, plus improved streaming decisions.

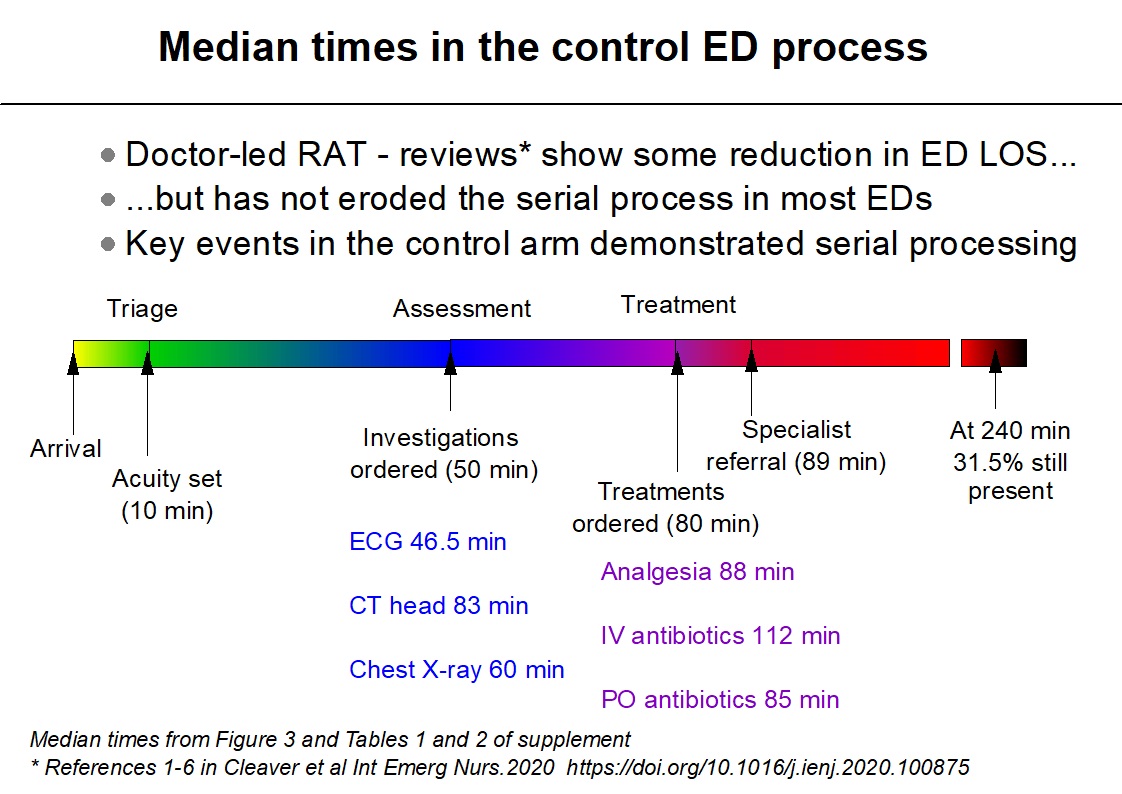

The ED cohort (470 patients): Although the trust had implemented doctor-led rapid assessment and treatment (RAT) so that a doctor and triage nurse saw ambulance patients, it was clear that serial processing of patients still predominated for the vast majority.

Arrival> Wait1> Triage > Wait2 > Investigations > Wait3 > Treatment

Very little happened at triage other than setting the acuity. Virtually all investigation requests occurred well after triage. Of concern are the long delays for time-critical orders. At four hours 31.5% of patients were still in ED. Those in the upper quartile for the arrival to investigation order interval (over 76 minutes) were much more likely to breach than patients in the lower quartile (under 18 minutes), 47% versus 26% respectively.

Proof of concept that at least a proportion of these investigations were successfully identified by band 5-7 nurses using a prototype touch-screen tablet app during a shorter time than triage has been published [6].

Although nominally the interval between arrival and the median time of setting the acuity using the trust’s standard procedure was 10 minutes, we know from additional time checks (where negative intervals were calculated) that arrival times were often inaccurate due to registration occurring later than arrival. We don’t feel that this was due to widespread ‘gaming’ of the system, but there are problems of using the arrival time in measures if this is inaccurate – see comment on ‘arrival time recording’ below.

The UTC cohort (904 patients): At the time of our study, June 2017, the process used GP-led streaming with options to ‘See & Treat’, have a second consultation with either a GP or nurse practitioner in the UTC, or send to ambulatory emergency care (AEC) or the ED.

Over-triage in UTC poses a significant burden on their co-located ED. Under-triage with the associated delay in eventual arrival at ED is a significant safety issue.

Once again very little in terms of investigation ordering was achieved at the streaming consultation. Few investigations other than urinalysis (103 patients) and Urine beta-hCG (33 patients) were ordered at streaming. Just 1 patient had a chest X-ray requested and only 25 patients had other X-rays ordered. One patient had an ECG at streaming, but for two patients ECG was only ordered during their second consultation (a median of 94.5 minutes after arrival). See & Treat was only used for 36/904 (4%) of patients.

Arrival> Wait1> Streaming > Wait2 > 2nd consultation

Wait1 had a median duration of 12 minutes (IQR 4-29)

Wait2 had a median 68 minutes (IQR 33-118)

Duration of stay: Of the 515 who remained in the UCT and for whom timings were valid/available the median stay was 123 minutes (IQR 85-174.5). Thus we concluded that most time spent in the UTC was spent waiting.

Of more concern was the poor standard of streaming decisions, particularly the excess of patients sent to the ED at streaming (156/904 17.3%) and after a streaming decision to keep them in the UTC – an additional 46 patients ended up in ED. Consultant review assessed only 43 patients as requiring ED from streaming. The GP-streamers largely ignored the AEC sending only 48/904 (5.3%) of patients, whereas the consultant deemed 162 (17.9%) patients suitable for AEC. Thus poor streaming decisions were contributing unnecessarily to ED overcrowding. For 67 patients who remained in the UTC after streaming but were then passed to different destinations (either AEC, ED or a different member of UTC staff) the patient journey must have been particularly unsatisfactory.

As a result of this information we have produced an adapted prototype designed to assist nurse-led streaming make better and more appropriate use of A&E facilities.

Software impediments to meeting the new standards

With the infrastructure and ED personnel currently available, the only initial assessments which can routinely be completed within 15 minutes are the basic triage or streaming encounters described above. This needs to change, but both new software and a new staffing model is required.

While we wait for sufficient Advanced Clinical Practitioner (ACP) recruits to be fully trained and doctor-led RAT remains a minimal contribution to patient flow, we also need to address shortcomings in the software and hardware infrastructure.

The nursing workforce spends too high a percentage of their time typing. We need to ask ‘is so much free text data entry really necessary?’ The temptation to simply translate old paper-based systems directly to on-screen formats is almost irresistible for managers and developers. The book-based Manchester Triage system has not always been translated well. Malcolm Senior who was chief information officer at Taunton and Somerset NHS Foundation Trust used to say that programmers working in nice quiet offices should not code software for ED staff. The same goes for NHS CIOs, but, in fairness, they have too many other issues to focus on. Nurses in ED work in a hectic, stressful and distracting environment and the software they use should reflect that and protect them.

Another question to ask: ‘Is free text data entry the most clinically useful format?’ The current faith in the Artificial Intelligence (AI) ‘cavalry’ to rush in and sort this out in future distracts the A&E field. There are simpler and currently available solutions which could be employed right now. These not only help with the immediate task of high speed clinical data entry (using mainly one-touch methods) but the consistent structure it imposes on the information can be readily used in the pattern recognition algorithms of AI going forward.

Studies using simultaneous processing of the same patients via SortED tablets and our NHS trust’s existing systems make this point. We gathered more clinically relevant data in less time than either triage nurses performed triage or GP-streamers took for their initial assessments. The actual data collection for symptoms and signs, vital signs recording, investigation and treatment selections generally took under 2 minutes, surprising even the app developers. In evaluating the control process we needed laborious abstraction of largely free text medical records and were therefore exposed to the difficulties of interpreting entries. In the UTC, the attempt of the software producer – Adastra – to impose structure (e.g. panels for the entry of vital signs) were largely ignored. GPs used an available free text field. This prevents field validation techniques checking for input errors and many of the entries were incomplete. Data quality and completeness are compromised.

NHS problems with lack of interoperability between systems is a major obstacle which needs urgent solution. Having a UTC use a different system for patient registration than the ED next door (FirstNet from Cerner who provide the trust’s EPR system) imposed unnecessary delay and duplication of effort. Those patients who walked in to the UTC and then ended up in the ED needed to be re-registered on Cerner. Direct data capture between the systems of London Ambulance Service (LAS) and the receiving trusts’ systems would also have helped reduce duplication of effort. Thankfully, albeit taking some years to solve, interoperability between the Trusts’ investigation and treatment ordering systems and the main EPR system has finally been achieved.

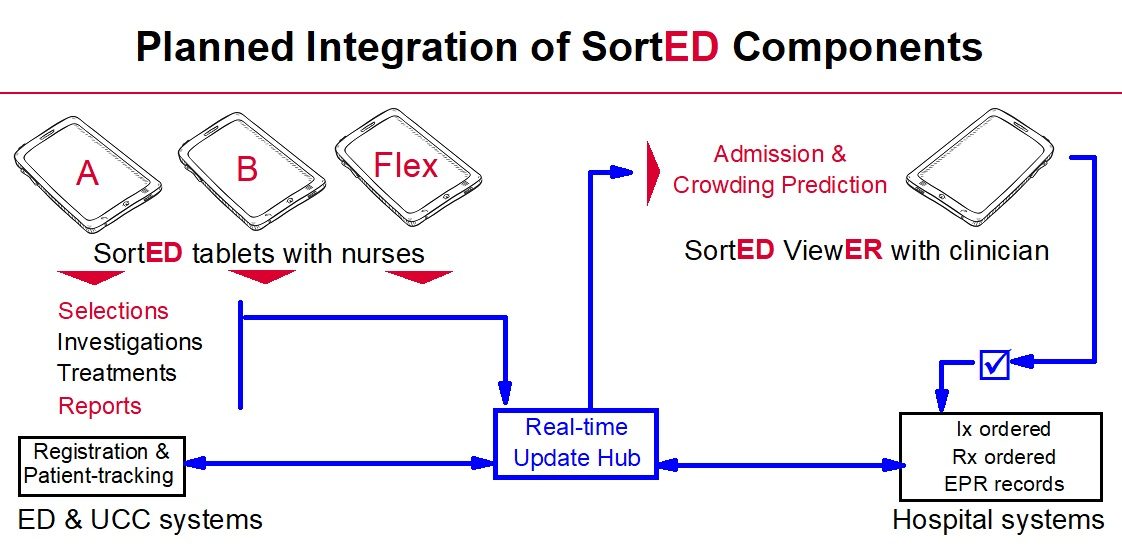

We believe that achieving more at initial assessment than conventional triage or GP streaming currently deliver is both achievable and desirable. Adding a touch screen specialist app for nurse-led RAT as a font-end to desk-based A&E systems will give the flexible solution needed in practice.

While we wait for more ACPs to be trained, we also suggest that an interlinked module for the lead clinician could assist less experienced nurses in ordering investigations and treatments and give the necessary authorisation. The lead clinician would also have access to warnings about impending intense overcrowding to flex up the workforce at the front door.

Ambulance handover % achieved in < 15 minutes

The impact of Exit Block and hospital-wide issues on ambulance handover is beyond the scope of this report. Patient off stretcher time (POST) is one measure used elsewhere and might be a more precise way to document handover.

Ambulance offload is a situation where a rapid, accurate and efficient process in conjunction with early organisation of investigations would be a potential benefit.

Crilly et al [7] studied the impact of the introduction of a dedicated ambulance offload nurse. This before, during and after observational study showed increases in offload compliance, a reduction in ED length of stay (ED-LOS) and a modest reduction in time to be seen by doctor. The role of the offload nurse not only included triage, but was a RAT-like process with early ordering of investigations (X-rays, pathology) and early provision of treatments such as analgesia. Assisting such a nurse with a tablet RAT support app such as ours should reap similar benefits.

This would be even more efficient if interoperability allowing some data transfer between ambulance service devices and the nurses’ tablets could be achieved.

Since % of ambulance handovers performed in < than 15 minutes and mean ED-LOS are both likely measures for inclusion in the new bundle of standards this is encouraging.

The problem of inaccurate arrival times

This was mentioned above and although it is not necessarily evidence of ‘gaming’ the four hour target, in the interest of data quality and because many of the new standards reference the patients’ arrival time, accuracy is desirable.

We have a particular interest in capture of real-time arrival data because in conjunction with SortED tablet case-mix and other information, forewarning of ED overcrowding could be delivered to ED managers. The plan is for them to flex up ‘front door’ nurses.

However when we began to design this system we assumed, incorrectly, that the arrival time data would be available and harvested from the trust’s EPR system. However it now transpires that there are recent problems there too.

To register a patient on the Trusts EPR system an attempt is made to identify the same patient’s Summary Care Record (SCR) via the NHS spine. These records are an electronic record of important patient information created from GP medical records. NHS numbers are assigned either at birth or when first registering with a GP. With a significant proportion of the London population not registered with a GP, this process can be quite difficult and hence introduce delay in entering the patient on to the system or in finding an existing Medical Record Number for patients previously seen in the Trust. The triage ‘encounter’ is not available until the record is found or created. Reception may also be swamped by sudden surges. While the patient is not yet on the system nurses resort to recording rough notes on pieces of paper.

We have a solution to this problem allowing the nurse to record a full initial assessment on their SortED tablet. The app allows swift enrolment with the available information, and generates a unique record which can have the MRN added when it becomes available. The SortED record can then be appended to the EPR.

While there is the current circa 40 minute gap between triage and investigation orders these minor delays in the bureaucracy of patient processing seem trivial and are not therefore being addressed. However, in order to deliver advanced warning of acute overcrowding we plan to link the ‘Front door’ nurse-led RAT app data directly with the advanced warning module for ED senior clinicians.

A missing element in the proposed bundle

One option set out in the consultation document [1] is for a ‘Numerical composite where a score is attributed to each measure and aggregated to a single number using weights’.

This approach is in danger of reproducing one of the problems of the four-hour standard in that case-mix is not being measured, so that comparisons between different trusts are not a fair measure of performance.

Better methods of triage and streaming which give more consistent measures of case-mix provide the potential for a fairer comparison between trusts.

A comment on agility

The major systems for electronic patient records are mammoth applications which take years to adapt and modify. This prevents new ideas being tested at the pace required. Emergency medicine is a dynamic specialty with a changing repertoire of diagnostic tests, equipment and treatments. Practices and ideas evolve. Even a new app like the SortED tablet needs to build in agility for the future. Equipment will change, methods of data entry will advance via direct transfer, we need to be prepared for these changes. But with rapid prototype evolution and testing of apps addressing specific issues like nurse-led RAT or streaming assistance we can prove which ideas make a fundamental difference to flow and overcrowding in A&E.

[1] NHS consultation document 2020 Available from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/transformation-of-urgent-and-emergency-care-models-of-care-and-measurement.pdf

[2] RCEM Feb 2021: RCEM Response to the Clinical Review of Standards consultation. Available from:

https://www.rcem.ac.uk/docs/Policy/2102_RCEM_response_CRS_consultation.pdf

[3] RCEM Sep 2018: Emergency Medicine Briefing: Making the Case for the Four-Hour Standard.

https://www.rcem.ac.uk/docs/Policy/Making%20the%20Case%20for%20the%20Four%20Hour%20Standard.pdf

[4] BMJ 2010;341:c3579 Targets still lead care in emergency departments

[5] British Journal of Hospital Medicine, November 2014, Vol 75, No 11 What has the 4-hour access standard achieved?

[6] Cleaver et al Int Emerg Nurs.2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2020.100875

[7] Crilly J, Johnston AN, Wallis M et al. Improving emergency department transfer for patients arriving by ambulance: A retrospective observational study. Emerg Med Australas 2020; 32(2):271-280.

Gillie Francis – Feb 2021